Baltimore Magazine, July 2015

By Mike Unger. Photography by Jennifer Hughes.

[]… It’s the kind of perfect-for-anything April Saturday in St. Michaels that inspires everyone who’s visiting town to describe it as “idyllic.” Streams of people flow into Lyon Distilling for a tour and a taste.

Wearing blue jeans and a broken-in baseball cap, Ben Lyon looks overworked. (And he is—he was up until 3 a.m. distilling.) But his mood soars the moment he starts explaining how the copper pot stills produce each and every drop of liquor this group of tourists is about to taste. A New Hampshire native, who once worked in public relations but whose heart has always been in craft brewing and distilling, Lyon takes the term “hand-crafted” quite literally. He executes every step of the process from fermentation to distilling to aging, approaching spirit-making with an almost Walter White-like respect for the scientific principles involved.

“Spirits marketers have taught us that older is always better,” he tells the group while holding a three-gallon oak barrel. (Standard barrels are 53 gallons.) “We want the 23-year-old Pappy Van Winkle, the 25-year-old Scotch. But aging is really a function of how much surface area of the wood the alcohol is exposed to. Because of the smaller surface area, we’re getting a more rapid aging process, so you literally can’t leave the spirit in these barrels for a long period of time, or else it will taste like you’re drinking an oak tree.”

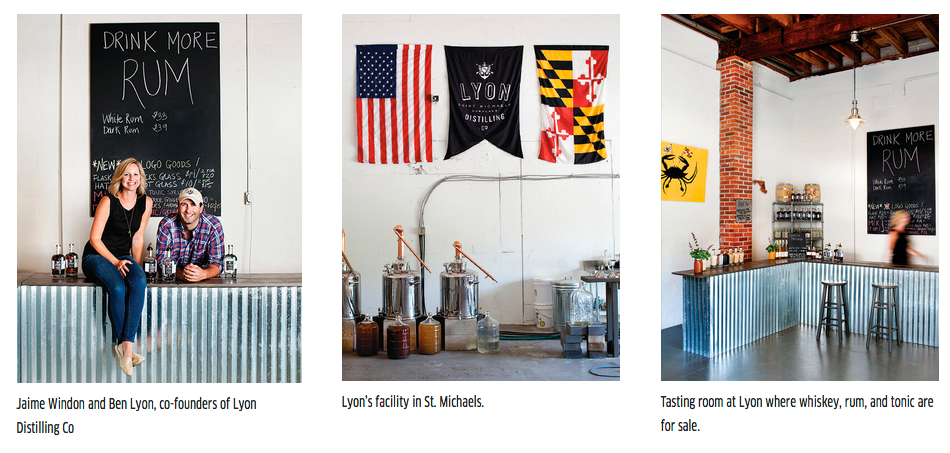

Thus, Lyon’s small-batch rye whiskey ages less than a year, his corn whiskey just a few days. For his rum, he uses a mix of molasses and sugar cane, resulting in a more flavorful and full-bodied spirit. Sitting at a table just a few feet away, his business partner and co-founder, Jaime Windon, bottles some by hand. They started the company in 2012.

“The world of liquor needed more options,” says Windon, a photographer by trade, who runs all operations aside from the actual distilling. “Up until a few years ago, almost every bottle on the shelf at the liquor store was owned by one of three or four booze conglomerates. Everyone wants to eat farm-to-table, drink local wine and beer, and liquor was that last missing component.”

Much like its alcohol brethren, craft distilleries gained a foothold on the West Coast. Their popularity has flowed east, and there are now more than 600 nationwide, with another 200 in the works, according to the American Distilling Institute. Last year, 1,600 people went to the organization’s conference in Louisville, KY, and attendance has been growing by roughly 30 percent a year.

Why the skyrocketing interest?

“We have the magic,” says Bill Owens, the organization’s founder and president. “You want to produce something that you’re proud of. Working in an insurance office doesn’t make it. There’s a comraderie that’s unparalleled.”

That spirit of cooperation can be found in the Maryland Distillers Guild, formed earlier this year by four distilleries, three wineries that also distill spirits, and two companies with pending licenses. Its charge is to grow both awareness of and the market for local spirits, and to lobby for legislative and regulatory changes at the state level. Current law allows distilleries to sell up to three bottles per person on site, but they’re prohibited from offering tastings at events like farmers’ markets, or from sampling their products in a mixed drink.

One question the guild won’t tackle, at least not at first, is what constitutes a craft distillery. In a world where words like “artisan” and “handmade” intoxicate customers, it’s a touchy subject.

“Craft is a term of reverence that defines not just the size of your distillery, but the manner in which you do things,” says Windon, the guild’s president. “For us, what defines craft is taking a raw ingredient to a finished product every step of the way.” …[]

READ THE FULL ARTICLE: http://www.baltimoremagazine.net/2015/7/6/maryland-distilleries-are-popping-up-everywhere